Part one: Violence and vilification Apparently, the time of the V-word has come. Now that Fred Khumalo has put him neatly in his callow place last Sunday, ANC Youth League president Julius Malema deserves no more attention. But it is hard to resist. I was searching for the right words myself when I fortuitously bumped into a minister who is archetypal of what one might now call the "veteran exile ANC set", has been a government minister since 1994 and who supplied me with the aptly pithy phrase: "Malema is a mindless fucking idiot."

Apparently, the time of the V-word has come. Now that Fred Khumalo has put him neatly in his callow place last Sunday, ANC Youth League president Julius Malema deserves no more attention. But it is hard to resist. I was searching for the right words myself when I fortuitously bumped into a minister who is archetypal of what one might now call the "veteran exile ANC set", has been a government minister since 1994 and who supplied me with the aptly pithy phrase: "Malema is a mindless fucking idiot."

This captures the essence of the ANC's current identity crisis. Remember how fond Thabo Mbeki was of asking "Will the centre hold?" I have come to appreciate that he was posing the question not only of South Africa but of his own organisation. So now we ask: Is the ANC the modern political party of sophisticates, well-versed in the ways of the world and able to "hold the centre"? Or is it a party of the lowest common denominator, willing to subjugate the Constitution's ideals of tolerance, rights and the rule of law to the rage of a populace that may have lost hope?

The right leadership would blend the savoir faire of the former with the anti-establishment zest of the latter. But at the moment it seems a zero-sum game, with the country trapped in the schism and struggling to breathe.

There is a good deal of snobbishness in the vitriol that now marks the differences between the two. The Mbeki set considers itself to be head and shoulders above the Zuma brigade, intellectually and strategically. Thus the veterans of Mbeki's exile crowd, and the loyalists of his 10 years in the West Wing, rail against the tide of vilification that now besieges their beleaguered leader.

And they have a point. Mbeki is seriously flawed; his legacy is all but bust; and he has made errors of judgement that should forever shame him. But he and his administration have done good things as well, which must be weighed in the balance.

Joel Netshitenze wrote recently in The Star that anyone who criticises the ANC wishes the ANC to be weak and is its opponent. Not so and not fair. At least for now, a strong ANC is a prerequisite for social cohesion. It may seem inappropriate to place such emphasis on a "mere" political party, and traditional liberals will balk at the notion, but this is no ordinary political party and when civic structures -- such as Sanco -- are weak, the ANC is needed to fill the gap.

After the recent violence against foreigners erupted, a survey of about 100 of Idasa's community leadership alumni elicited this primary, common observation: that where local government and/or the ANC is strong, there were no attacks; it was where the structures were weak or absent that the bulk of the violence took place.

Hence, this week it was the ANC leadership that the South African Human Rights Commission met with to discuss the Khutsong protests. The commission, the leadership of which deserves commendation for speaking up against the "ready to kill" talk by Malema and others, were deeply troubled by the reaction of the Khutsong community to the judgement of the Constitutional Court concerning its provincial boundaries.

Accusing the Constitutional Court of "vilifying" Justice John Hlophe, as Kgalema Motlanthe did last week, is as unhelpful as it is a disappointing and uncharacteristic lapse of composure and judgement. One day you are slagging off the Constitutional Court, Mr Motlanthe, the next the SAHRC is seeking you out to discuss how your organisation can help persuade a community to accept peacefully the judgement of the court. Do you see the problem?

In a violent and precarious society the very last thing you need is for people in leadership positions to appear to offer exhortation to murder or to undermine the rule of law. And yet again there is little but silence from Jacob Zuma. Yet again there are questions about his fitness for public office. Why does he stay silent? Because these expressions of violence represent a thinly veiled threat to the current establishment and especially the judiciary, which is seen as potentially the last real obstacle to a Zuma presidency.

Part two: Peace-making abroad What is so striking is that some of the men of violent words south of the border are the same people who are quick to criticise Robert Mugabe for his violence against his own people. Are they blind to this connection? Do they not at the very least see how the connection would be made?

What is so striking is that some of the men of violent words south of the border are the same people who are quick to criticise Robert Mugabe for his violence against his own people. Are they blind to this connection? Do they not at the very least see how the connection would be made?

Given the events in Zimbabwe, there is now a strong case for an international peace-making initiative. A recent paper by Piers Pigou (Defining Violation: Political Violence or Crimes against Humanity? available online at www.idasa.org.sa under State in Transition Observatory/research reports) thoughtfully, carefully and persuasively makes the case for external intervention. The kernel of the argument is that Zimbabwe, whether it matches the high test of "crime against humanity" or not, has failed in its "responsibility to protect". This is a relatively new doctrine of international law, developed as a reaction to the failure of the international community to prevent genocide in Rwanda and in the former Yugoslavia, and permits collective intervention where a state has failed to protect its citizens from serious harm.

The idea is that state sovereignty implies responsibility and where that responsibility is breached, through state-sponsored torture or a failure to act to prevent internal repression or violence, the international community has authority to intervene. There is now ample evidence that this state of affairs prevails in Zimbabwe. In truth it has for quite a while and, for me, the arrest of Tendai Biti, the Movement for Democratic Change's dynamic secretary-general and a young man who has impressed many in the Department of Foreign Affairs in Pretoria, including the deputy minister, was the absolute last straw. He is no traitor; he is a decent, committed, progressive democrat.

So, thus, does Mbeki's failure becomes more acute. His strategy has been that of a one-trick pony: get the Zimbabwean political leadership to negotiate and enter into a government of national unity. But this fails to appreciate that a legitimate negotiation requires a reasonably level playing field. That has never been allowed for the MDC, with Mbeki's connivance. He doesn't like or trust the MDC. Some, such as his brother, believe this is a projection of his discomfort with leftist or trade unionist opposition at home. Others think that he believes, as Mugabe claims, that the MDC is a tool of the West. Well, the MDC has certainly received plenty of Western support, direct and indirect, including from the British. But so has the ANC, now and in the old days. Did that make them, the ANC, a tool of the West? And now, what about those British -- and German and Italian and Swedish -- weapons systems that were bought at the turn of the century? Isn't it time that they were employed, in the name of international law and liberal interventionism, to protect the Zimbabwean people? Or was the arms deal only about filling the empty coffers of the ANC?

This is not a call for a "regime change-style military intervention", à la Iraq, but a peace-making and peace-keeping force to create the conditions of stability and tolerance necessary to permit a (delayed) free and fair election and the protection of fundamental human rights.

The peril of my deadline means that in the three days before this column can be read, much could happen. Yet Morgan Tsvangirai's withdrawal from the presidential run-off is not only a justified statement of principle but a tactical retreat ahead of a multilateral intervention. There is a real sense that some SADC leaders, hitherto discouraged by Mbeki's stance, are so outraged that they regard Mbeki's position not only to have failed but to be wrong in principle. On this Mbeki may find that he is behind the curve of regional opinion, while in the capitals of the West his apparent appeasement simply serves to undermine his passionate desire to win respect for Africa and its people by playing into all the worst possible racist stereotypes of this continent and its leaders.

Part three: Business and PPP

The business sector is struggling to make sense of the latest acronym: PPP -- Post-Polokwane Politics. To many business leaders the two centres of power make their brains frazzle.

The business sector is struggling to make sense of the latest acronym: PPP -- Post-Polokwane Politics. To many business leaders the two centres of power make their brains frazzle.

Dealing with one set of government relationships is demanding enough, but two? We want to engage constructively, say some, but we're unsure who we should be talking to. The global recession and the power shortages and high interest rates serve to make everything seem that much less cheerful. Uncertainties and anxieties escalate. Business sentiment and business confidence are fragile and fickle.

Whatever one may think of capitalism, at this point South Africa needs a vibrant corporate sector, willing to invest in skills and in new, sustainable business models.

Some business leaders appreciate that the post-Polokwane ANC and the policy resolutions that accompanied the change in leadership do not represent an ideological sea change. But they are also aware it is the execution of policy that matters most. As one normally robust and sanguine chief executive put it to me earlier this week: "The Expropriation Bill: put it in the hands of a Mathews Phosa, fine; but put it in the hands of Julius Malema …"

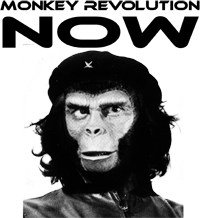

And he's quite right; people in power do matter. And that, Mr Malema, is the other consequence of your words: you undermine business confidence -- how does that help your "revolution"? Go and play Che Guevara somewhere else.

0 comments:

Post a Comment